Main Page

- Why Don't Russians Smile: ~149 pages. https://bit.ly/2YGSAYE (Draft 9)

Why Don't Russians Smile

Title Page

| e |

|

The definitive guide to the differences between Russians and Americans - 2nd edition

|

Russia is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma

- — Winston Churchill, October 1939.

I have never met anyone who understood Russians.

- —Grand Duke Aleksandr Mikhailovich Romanov (1866–1933)[1]

Acknowledgements

Table of Contents

e |

|

Table of contents

|

Introduction - “I have never met anyone who understood Russians.” - Collectivism versus Individualism.

e | |

|

“Don't bring your own rules into a strange monastery” (В чужой монастырь со своим уставом не ходят)[2] MANY AMERICANS have returned from a first visit to Russia exclaiming, "I don’t understand why we have had such difficulties with the Russians. They are just like us." Subsequent visits, and a closer look, will reveal that Russians and Americans do indeed have stark differences. This book will seek to explain those differences and to help Americans understand why Russians behave like Russians. In the process, American readers may also learn why they behave like Americans. After all, as one sociologist explained, “To know one country is to know none”.[3] The surface similarities between Russians and Americans are readily apparent:

In Russia there is the desire “to find the balance between the conflicting outlooks of Europe and Asia, between Western claims to personal freedom and Oriental insistence on the integration of the individual into the community.” --Nicolas Zernov (1898-1980), Russian Orthodox theologian.[5]

The topic of collectivism will be discussed in a later chapter. Cultural differences matterOne reader commented, “Speaking of cultural differences leads us to stereotype and therefore put individuals in boxes with ‘general traits.’ Instead of talking about culture, it is important to judge people as individuals, not just products of their environment.” At first, this argument sounds valid, even enlightened. Of course individuals, no matter their cultural origins, have varied personality traits. So why not just approach all people with an interest in getting to know them personally, and proceed from there? Unfortunately, this point of view has kept thousands of people from learning what they need to know to meet their objectives. If you go into every interaction assuming that culture doesn’t matter, your default mechanism will be to view others through your own cultural lens and to judge or misjudge them accordingly. Ignore culture, and you can’t help but conclude, “Chen doesn’t speak up—obviously he doesn’t have anything to say! His lack of preparation is ruining this training program!” Or perhaps, “Jake told me everything was great in our performance review, when really he was unhappy with my work—he is a sneaky, dishonest, incompetent boss!” Yes, every individual is different. And yes, when you work with people from other cultures, you shouldn’t make assumptions about individual traits based on where a person comes from. But this doesn’t mean learning about cultural contexts is unnecessary. If your business success relies on your ability to work successfully with people from around the world, you need to have an appreciation for cultural differences as well as respect for individual differences. Both are essential. As if this complexity weren’t enough, cultural and individual differences are often wrapped up with differences among organizations, industries, professions, and other groups. But even in the most complex situations, understanding how cultural differences affect the mix may help you discover a new approach. Cultural patterns of behavior and belief frequently impact our perceptions (what we see), cognitions (what we think), and actions (what we do). The goal of this book is to help you improve your ability to decode these three facets of culture and to enhance your effectiveness in dealing with them.[9]

|

Chapter 1: Russian Coconuts & American Peaches - Why don’t Russians Smile?

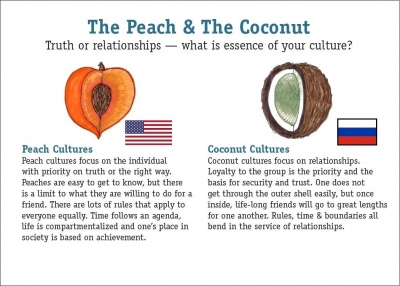

Why are Americans like peaches and Russians are like Coconuts?

e | |||||

The best and most memorable way to think of the differences between Russian and America is that America is a “peach” culture and Russia is a “coconut” one. This analogy was created by two culture experts.[11] In peach cultures like the United States or Brazil people tend to be friendly (“soft”) with new acquaintances and strangers. They smile frequently at strangers, move quickly to first-name usage, share information about themselves, and ask personal questions of those they hardly know. Americans tend to be specific and emotional, which translates as enjoying other people, whereas Russians are diffuse and neutral, which translates into respect (esteem) of other people. Culturally speaking, America is like a peach with lots of easily accessible flesh or “public domain” on the outside but a tough, almost impenetrable stone at the core. In contrast, Russians are difficult to penetrate at first but all yours if and when you manage to drill your way through to their core. By the way, a little alcohol helps to lubricate the drill.[12] For a Russian, after a little friendly interaction with a peach, they may suddenly get to the hard shell of the pit where the peach protects his real self and the relationship suddenly stops. In coconut cultures such as Russia and Germany, people are initially more closed off from those they do not have friendships with. They rarely smile at strangers, ask casual acquaintances personal questions, or offer personal information to those they don’t know intimately. But over time, as coconuts get to know you, they become gradually warmer and friendlier. And while relationships are built up slowly, they also tend to last longer.[13] Coconuts may react to peaches in a couple of ways. Some interpret the friendliness as an offer of friendship and when people don’t follow through on the unintended offer, they conclude that the peaches are disingenuous or hypocritical. Many Russians see the American Smile as disingenuous and fake.

|

Beyond Fruit - Why don’t Russians smile?

e |

|

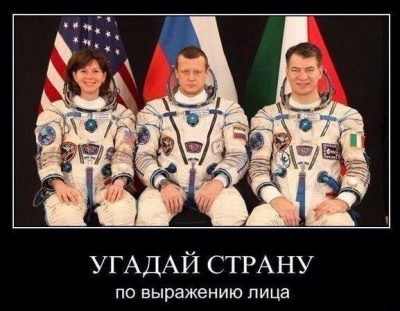

Russians don’t smile much, but that doesn’t mean they don’t like you. In preparation for the 2018 World Cup in Russia, Russian workers were taught how to properly smile at the foreign soccer fans who would soon be visiting their country. In 1990, when McDonalds opened its first franchise in Moscow, workers had to be trained to be polite and smile. Russians will be quick to tell you that in Russia, randomly smiling at strangers is often viewed as a sign of mental illness or inferior intellect. To Americans, it might be easy to assume that this says something about Russians — that they are an unfriendly, callous people. But that’s not true at all. Instead, it may be worth looking at why certain expressions, such as smiling, become a key part of social exchanges in some cultures and not others.[16][17][18] Some authors have quipped that Russia is a "Bitchy Resting Face Nation". Resting bitch face is a facial expression that makes a person unintentionally appear to be angry, annoyed, irritated, or feeling contempt, especially when the individual is relaxed.[19] So why are Russians like “coconuts” and Americans like “peaches”? Why do Russians often think Americans are either idiots and insincere? Why do Americans feel that Russians are unfriendly and cold? Thankfully there are many social science theories that have explored this topic. These include immigration and collectivism vs. individualism.

|

Immigration

e |

|

Studies have shown that countries such as America with high levels of immigration historically are forced to learn to rely more on nonverbal cues. Thus, you might have to smile more to build trust and cooperation, since you don’t all speak the same language. First, picture an American cowboy out on the range coming across a lonely Indian. At the beginning of their encounter he may wave and then smile as he cautiously approaches to show that he has no ill intention. Or one can imagine an immigrant with limited English arriving and desperately looking for work. They quickly come to realize the value of smiling to show their alacrity to work and their new patrons smile to show they approve of their services. In contrast, in historical homogenous Russian villages (mir), Russians knew the same people and lived among the same people for generations. The village was similar to one big family. A Russian did not have to hide their feelings among the large village family members.[20]

|

Soviet Propaganda - Americans’ smile hides deceit

e |

|

In general, the American smile has a terrible reputation in Russia. This campaign started in the early Soviet era. There were sinister smiles on old agitprop (political communist art and literature propaganda) posters of caricature "U.S. imperialists" wearing trademark cylinder hats, smoking cigars, salivating and smiling as they relished their piles of money and power over the world’s exploited classes. Later, starting from the Khrushchev and Brezhnev eras and continuing until the late 1980s, the Soviet print and television media carried regular reports called “Their Customs,” explaining that Americans, a power-hungry people, smiled to deceive others. Soviets were told that behind the superficial American smile is an “imperialist wolf revealing its ferocious teeth.” The seemingly friendly American smile, Soviets were told, is really a trick used to entice trusting Soviet politicians to let their guard down, allowing Americans to deceive them both in business deals and in foreign policy. An example that Russian conservatives love to quote is when then-U.S. Secretary of State James Baker in February 1990 reportedly used his “charming, cunning Texas smile” to trick then-Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev into agreeing to a unified Germany as long as the United States pledged verbally that NATO would not extend “an inch further” to the east. The image of an insincere, insidious American smile was used in Soviet propaganda mainly to depict U.S. politicians, “warmongers” from the military-industrial complex and other “bourgeois capitalists,” but it also applied to normal Americans, who, Soviets were told, use smiles to betray one another in business and personal relations. The message was clear: Feel fortunate you live in the Soviet Union, which has an honest moral code of conduct, where people trust one another and where there is complete harmony at work and among different nationalities. Unlike the American smile, the Soviet smile was sincere, according to the official propaganda, because Soviets had so much to be happy about — guaranteed jobs and housing, free education, inexpensive sausage, a nuclear war chest to protect the empire, and Yury Gagarin, who beat the Americans to space. During the perestroika era of the 1980s, the American smile was a common reference point when the topic of rude Soviet service was discussed. In post-Soviet Russia, business motivational speakers often preach the value of implanting U.S. know-how — the “technique of smiling” — among employees in stores, restaurants and other service-oriented companies. In this spirit, McDonald’s restaurants in the 1990s even included a “smile” on its Russian menu together with the price: “free.”[21][22] |

America is the most individualistic nation in the world, whereas Russia has no word for privacy

e |

|

American culture tends to be more extraverted. Americans are more likely to seek contact with strangers and outsiders as a way of building success. They are more extraverted and adventurous as a nation. Americans, especially in the western states, tend to embrace their connection to their frontier past and idealize the individual exploring their limits and seeking their own fortune. There is a sense that one can rise and fall on their own merits. In a culture that prizes individualism so highly, there are no predetermined social links. In addition 24 percent of Americans move every 5 years, making it one of the most geographically mobile countries.[23] Americans must always be ready to invest in new social ties. In contrast, Russians have a tendency to function in tight social units. Think of a large family living in close quarters and working together. There is a close association with the welfare of the group and individual well-being. Ethics are largely seen as expressions of loyalty to your family and social network and not to individual ideals (For example, Russians are more likely to cheat or lie for a friend). In close living and cooperation the sense of privacy disappears. In fact, a word for privacy doesn’t even exist in Russian "Untranslatable ideas" section. There is a sense of a shared existence and no need to emphasize a positive attitude or ornament your facial expressions and interactions because much is taken to be understood. There is less of a sense that a smile is needed. However, that does not mean that Russians don’t have a need for individual privacy or protection from unwanted scrutiny. Given that Russians have no expectation of privacy in their homes, apartments, workplace, or in public spaces, their sense of privacy lies closer to their own skin. They feel less obligated to share their personal feelings and may have seemingly impenetrable expressions on their faces. A century before the virus Covid-19 made the term “social distance” popular, sociologists used the term in a completely different way. Sociologists call a county’s individualist versus collective characteristics as “social distance”.[24][25] Social distance is measured by the expectation of privacy in a country. The lower the social distance, the less privacy in a country. Studies have found that in Russia, social distance is lower relative to the U.S. Russians rely on more mutual understanding and longer shared national history to a much greater extent than Americans. Thus, there’s less pressure to display a positive emotion like smiling to signal friendliness or openness, because it’s generally assumed a fellow Russian is already on the same wavelength.[26][27] When there’s greater social distance there is a greater sense that it is up to the individual to seek their own fortune as opposed to the collective group in a nation. There’s more of a live and let live mentality. Americans expect a certain amount of privacy, even in public places; “one needs to mind their own business”. This can also lead to a sense of social anxiety and isolation and strangers can seem more strange or foreign than they are in reality. There may be more wiggle room to get into trouble during a chance new encounter with a stranger. When it does happen, it can be anxiety-inducing. Therefore, the common wisdom when approaching strangers is to smile and express warmth in a way that can help the other person feel at ease.[28] The American smile is habitual. Americans are commonly required to smile at work. More smiles means more comfortable transactions and happier customers, which translates to more money for the owner. Nonetheless, when interacting with other cultures, your American smile may be misinterpreted as arrogance. In countries with greater cultural uniformity, people sometimes smile, not to show cooperation, but that they don’t take the other person seriously or that they are superior. If you live in Russia very long you start hearing that American smiles are “fake”. Russians may wonder what is hidden behind a smile. But for the average American, there is nothing behind the American smile. It is a habitual form of communication. However, even in America there are some regional differences in regards to the smile. People from “American heartland” may see a smile differently than a big city urban smile.[29] Americans have a term called "PASSIVE AGGRESSIVE" Пассивно-агрессивное поведение – people from the capital of America – where one of the authors worked for 8 years – are very Пассивно-агрессивное. They will smile as they stab you in the back.

"Why should I smile at someone I don't know? I'm not a clown. If I'm ready for a serious conversation I have to look serious."[30]

|

Your American smile may be misinterpreted as arrogance

e |

|

When interacting with other cultures, your American smile may be misinterpreted as arrogance. In countries with greater cultural uniformity, people sometimes smile, not to show cooperation, but that they don’t take the other person seriously or that they are superior.

|

Chapter 2: Russians and Americans

Westernizers and Slavophiles

e |

|

To Russia, in its hunger for civilization, the West seemed “the land of miracles.…”

Russia’s love-hate relationship with the United States and the West has given rise to two schools of thought: Westernizers (зáпадничество) and Slavophiles (Славянофильство). Beginning in the second half of the 19th century, both can be regarded as Russian patriots, although they have historically held opposing views on Russia’s position in the world. Both groups, recognizing Russia’s backwardness, sought to borrow from the West in order to modernize. Historically Russian Westernizers sought to borrow from the West to modernize. They felt Russia would benefit from Western enlightenment, rationalism, rule of law, technology, manufacturing, and the growth of a middle class. Among the Westernizers were political reformers, liberals, and socialists. Slavophiles also sought to borrow from the West, but they were determined to protect and preserve Russia’s unique cultural values and traditions. A more collective group, they rejected individualism and regarded the Church, rather than the state, as Russia’s leading historical and moral force. Slavophiles were admirers of agricultural life and were critical of urban development and industrialization. Slavophiles sought to preserve the mir (Agricultural village communes, see Chapter 3, Collective vs. Individualist) in order to prevent the growth of a Russian working class (proletariat). They opposed socialism as alien to Russia and preferred Russian mysticism to Western rationalism. Among the Slavophiles were philosophical conservatives, nationalists, and the orthodox church. The controversy between Westernizers and Slavophiles has flared up throughout Russian history. These two schools of thought divided Russian socialism between Marxists and Populists, Russian Marxists between Mensheviks (1903-1921) and Bolsheviks, and Bolsheviks between opponents and followers of Stalin. The controversy has been between those who believed in Europe and those who believed in Russia.[31][32] Today the conflict continues between supporters and opponents of reform, modernizers and traditionalists, internationalists and nationalists. Today’s conservative Russians who seek to preserve Russia’s faith and harmony are ideological descendants of the Slavophiles. For them, the moral basis of society takes priority over individual rights and material progress, a view held today by many Russians, non-communist as well as communist. As Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918 – 2008) said from his self-imposed seclusion in Vermont, 15 years after his forced exile from the Soviet Union:

This school of thought has given Russia a superiority complex toward the West in things ethereal and an inferiority complex in matters material. The West is seen as spiritually impoverished and decadent, and Russia as morally rich and virtuous.

|

Chapter 3: Russians’ Unique Culture and Character (Social Etiquette and Expectations)

The Russian is a delightful person till he tucks in his shirt. As an oriental he is charming. It is only when he insists upon being treated as the most easterly of western peoples instead of the most westerly of easterns that he becomes a racial anomaly and extremely difficult to handle. The host never knows which side of his nature is going to turn up next. — Rudyard Kipling, The Man Who Was. (1900)

The Russian Soul

e | |||||

|

The famous “Russian soul” was to no small extent the product of this agonizing uncertainty regarding Russia’s proper geographical, social, and spiritual position in the world, the awareness of a national personality that was split between East and West. —Tibor Szamuely, The Russian Tradition (1974). Just because Russians “don't smile” does not mean that inwardly they are soulless drones or secretly conniving. Russians smile when they have a genuine reason. Russian smiles are authentic. Furthermore, although they deeply value intellectualism and education (erudition), they are leery of (antithetical towards) being ruled by logic. In fact, Russians value the ability to fully experience and act on their passions and emotions. The Russkaya dusha (Russian soul) is well known in the arts, where it manifests itself as emotion, sentimentality, exuberance, energy, the theatre and flamboyant skill. But Russian soul is much more than just the arts. It is the very essence of Russian behavior. The Russian soul can turn up suddenly in the most unexpected places—and just as suddenly disappear. Just when foreigners believe that Russians are about to get down to serious business, they can become decidedly emotional and unbusinesslike.

The Russian soul is often derided in the West as a fantasy of artists, composers, and writers. If the Russian soul ever really existed, this argument goes, it was the product of a traditional agricultural society that had very little in material goods to offer. In a modern industrial society the Russian soul is quickly forgotten and Russians become as realistic, practical, materialistic, and unromantic as Westerners.[34][35] As in many aspects of Russia, the truth is more complex and lies somewhere in between. Russians do have a rich spirituality that does indeed contrast with Western rationalism, materialism, and pragmatism. Russians suffer but based on the amount their popular literature discusses suffering, Russians seem to enjoy this suffering. Obsessed with ideas, their conversations are weighty and lengthy. Russians often reject the American’s rational and pragmatic approach. Instead personal relations, feelings, and traditional values determine their course of action. In contrast, Westerners tend to view themselves as pragmatic, relying on the cold facts.[36][37]

Even today emotions and personal feelings still matter to Russians. The future of the Russian soul brother Russians. It has survived centuries of church and state domination and 70 years of communism. Will it also survive, they wonder, the transition to the free market and democracy, and the call of Western culture?[46]

There is definitely a set of characteristics, often referred to as “the Russian soul”, that make Russians unique. Expats who say there isn’t, as well as Russians who say foreigners will never be able to understand it (умом Россию не понять), are both wrong.[49] |

Collective vs. Individualist

e | |

|

[For Russians] the striving for [group] activity has always prevailed over individualism.

[Russia has always valued the] communal way of life over the merely individual. Community was seen so near to the ideal of brotherly love, which forms the essence of Christianity and thus represents the higher mission of the people. In this “higher mission” a commune—a triumph of human spirit—was understood as opposing law, formal organizations, and personal interests.

Sobornost (communal spirit, togetherness) distinguishes Russians from Westerners in which individualism and competitiveness are more common characteristics. Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville. Democracy in America. 1835: I know of no country in which there is so little independence of mind and real freedom of discussion as in America. The Americans, in their intercourse with strangers, appear impatient of the smallest disapproval (censure) and impossible to satisfy hunger for praise (insatiable) ... They unceasingly harass you to extort praise, and if you resist their humble request (entreaties) they fall to praising themselves. It would seem as if, doubting their own merit, they wished to have it constantly exhibited before their eyes. It seems, at first sight, as if all the minds of the Americans were formed upon one model, so accurately do they correspond in their manner of judging. A stranger does, indeed, sometimes meet with Americans who dissent from these rigid beliefs (rigorous formularies); with men who deplore the defects of the laws, the ability to change (mutability) and the ignorance of democracy; who even go so far as to observe the evil tendencies which impair the national character, and to point out such remedies as it might be possible to apply. But no one is there to hear these things besides yourself, and you, to whom these secret reflections are confided, are a stranger and a bird of passage. Americans are very ready to communicate truths which are useless to you, but they continue to hold a different language in public. In America the majority raises formidable barriers around the liberty of opinion; within these barriers an author may write what he pleases, but woe to him if he goes beyond them. In the United States, the majority undertakes to supply a multitude of ready-made opinions for the use of individuals, who are thus relieved from the necessity of forming opinions of their own. Americans are so filled with love for (enamored) with equality that they would rather be equal in slavery than unequal in freedom. The surface of American society is covered with a layer of democratic paint, but from time to time one can see the old aristocratic colors breaking through. An American cannot converse, but he can discuss, and his talk falls into a dissertation. He speaks to you as if he was addressing a meeting... As one digs deeper into the national character of the Americans, one sees that they have sought the value of everything in this world only in the answer to this single question: How much money will it bring in?

The contrast between Russian communalism and American individualism can best be seen in the historical differences between Russian peasants (serfs) and American farmers. America’s settlers were independent farmers and ranchers who owned their own land and lived on it, self-sufficient and distant from their neighbors. In contrast to the Russian peasants of the mir (a medieval agricultural village commune), American farmers lived behind fences that marked the limits of their property. The Americans were entrepreneurs in the sense that they managed their property individually, taking economic risks and self-regulating their own lives, independent of the state and without being dependent on the community. Although the United States also has had its own communes, these communes have existed on the fringes of society rather than at its center. In the United States, the commune is considered alien (except for Native Americans, who also lived a communal lifestyle). To Russians, the commune is a deep part of their psyche. Individualism is esteemed in the West, but in Russian the word has a negative (pejorative) meaning. Steeped in the heritage of the communal village, Russians think of themselves as members of a community rather than as individuals. Individualism is equated with selfishness or lack of regard for the community. Communal culture helps explain many of Russian’s characteristics, for example their behavior in crowds. Physical contact with complete strangers—repellent to Americans and West Europeans — does not bother Russians. When getting onto the subway complete strangers may touch, push, shove, and jostle about like siblings competing for the last morsel of chicken. They may elbow you without serious reflection or fear of resentment. A crowd of passengers attempting to board a ship in Odessa, Ukraine in the early 1960s caught the attention of South African author Laurens van der Post:

Foreign visitors who dislike close contact should avoid the Moscow Metro (subway) especially during rush hours, when trains run every 90 seconds but the metro is generally still crowded the rest of the day. Americans have a distinct line between work and personal relationships. In contrast, after working together all day, Russian factory and office employees will spend evenings in group excursions to theaters and other cultural events organized by their supervisors or groups, such as in the artel (workers’ cooperatives). Russians seem compelled to intrude into the private affairs of others. Older Russians admonish young men and women, complete strangers, for perceived wrongdoings, using the term of address molodoy chelovek (young man) or dyevushka (girl). On the streets, older women volunteer advice to young mothers on the care of their children. In a collective society, everybody’s business is also everyone else’s.

|

Russian pessimism - A pessimist is an informed optimist

e |

|

We did the best we could, but it turned out as usual. (Хотели как лучше, а получилось как всегда.)

Russian pessimism is the source of many Russian jokes (anekdoti). According to one, pessimists say, “Things can’t be worse than they are now.” Optimists say, “Yes they can.” Another antidote describes a pessimist as an informed optimist. It is no secret, of course, that Americans love happy endings -- to the point of childishness, many Russians say. Russian pessimism contrasts with American innocence, naivety, and optimism. Americans expect things to go well, and they become annoyed when they do not. Russians expect things to go poorly and are prepared for disappointments. This can be seen in Russian horoscopes which unlike their American counterparts seem full of gloom and doom. To American astrologers, a dangerous alignment of the planets offers an obstacle to overcome - another opportunity for personal growth. Contrast this with a typical horoscope in the 1994 Kommersant newspaper:

Similarly, like the ancient Greeks Russian's literature is full of tragedy. Russian history shows that life has indeed been difficult for Russians. Weather, wars, violence, cataclysmic changes, and oppressive rule over centuries have made pessimists out of Russians. Richard Lourie explains that:

Fear is a major element of the Russian psyche, and will be encountered in many places in Russia, especially at the highest levels of government, where there is often fear of an outside enemy determined to destroy Russia. Americans should not be put off by this gloom and doom, nor should they attempt to make optimists of Russians. The best response is to express understanding and sympathy. Less in control of their lives than other Europeans and Americans, Russians feel caught up in the big sweeps of history where the individual is insignificant and does not count. Translators Richard Lourie and Aleksei Mikhalev explain:

Glasnost and perestroika were exciting for foreigners to observe from a distance, but to Russians they were yet another historical spasm with uncertainties about the future in which outsiders, this time America, betrayed many promises. The best and brightest Russians have traditionally been banished. In old Russia independent thinkers were exiled to Siberia. Hollywood was created by Jews escaping Russia. Following the Bolshevik Revolution, the cream of Russia’s elite was liquidated. Stalin’s purges of the 1930s further decimated the intelligentsia, and today many of Russia’s best and brightest have been lost through brain drain emigration. One of those who emigrated was Vladimir Voinovich, a human rights advocate who was forced to leave for the West in 1975 after the KGB threatened that his future in the Soviet Union would be “unbearable.” Voinovich wrote:

This gloomy and dark side of the Russian character explains the bittersweet humor that is native to Russia and the “good news, bad news” jokes. Russian pessimism can also be infectious, and Americans who have worked with them for many years are vulnerable to the virus. Llewellyn Thompson, twice American ambassador to Moscow, was asked on his retirement in 1968 to name his greatest accomplishment, “That I didn’t make things any worse.” [61] Despite their pessimism and complaining, there is an admirable durability about Russians, a hardy people who have more than proven their ability to endure severe deprivation and suffer lengthy hardships. Tibor Szamuely wrote of “the astonishing durability of certain key social and political institutions, traditions, habits, and attitudes, their staying power, their essential stability amidst the turbulent currents of violent change, chaotic upheaval, and sudden innovation.”[62] |

Russians Lie

e |

Russians lie, a national characteristic called "vranyo". Dictionaries translate vranyo as “lies, fibs, nonsense, idle talk,” but like many Russian terms, it is really untranslatable. Americans might call it “tall talk” or “white lies,” but “fib” perhaps comes closest because vranyo. To these words may be added the Irish "blarney", which comes nearer than any of the others, but still falls pretty wide of the mark. As Russian writer Leonid Andreyev noted, is somewhere between the truth and a lie. Vranyo is indeed an art form, beautiful perhaps to Russians but annoying to Westerners and others who value the unvarnished truth.[67] In its most common form today, vranyo is an inability to face the facts, particularly when the facts do not reflect favorably on Russia. Tourist guides are masters of vranyo, as are Russians who represent their country abroad. When ideology or politics dictate a particular position, they are likely to evade, twist, or misstate facts in order to put the best possible spin on a potentially embarrassing situation. As Boris Fyodorov, the 1998 deputy prime minister of Russia explained, "There are several layers of truth in Russia. Nothing is black or white, fortunately or unfortunately."[68] Russians, however, do not consider vranyo to be dishonest, nor should foreign visitors. As the famous Fyodor Dostoyevsky explained:

When using vranyo, Russians know that they are fibbing and expect that their listeners will also know. But it is considered bad manners to directly challenge the fibber. As one Russian specialist suggest advises, the victim of vranyo should "convey subtly, almost telepathically, that he is aware of what is going on, that he appreciates the performance and does not despise his...host simply because the conditions of the latter’s office obliged him to put it on."[70][71]

|

Verification - Trust but Verify

e |

|

Trust, but verify. (Доверяй, но проверяй).

Can Russians be trusted to honor commitments? The prudent response to this question is “Yes, but. …” According to Zbigniew Brzezinski, US Former National Security Advisor, Anglo-Saxons and Russians have different concepts of trust:

Related to verification are accountability and reporting, particularly where the expenditure of funds is involved. Russians can be notoriously lax about accounting for expended funds and using them effectively, a problem recognized by Mikhail Gorbachev. A problem is accountability of funds. American donors to Russian philanthropic institutions have reported difficulties in obtaining prompt and detailed reporting on how their funds are being expended. Some new Russian foundations have scoffed at the standard regulatory and accounting procedures required by American donors. As one Russian foundation official put it, "We are all fine Christian men, and our [Russian] donors don’t question what we do with their money."[73] Such a response should not be seen as an intent to deceive but rather as an intercultural difference. Americans understand the need for accountability, annual financial reports, and audits by certified public accountants. But requesting such procedures from Russians may be seen as questioning their good faith and honesty. When encountering indignation over reporting requirements, Americans may wish to emulate Ronald Reagan by responding, “Trust, but verify.”

|

Cheating in Universities

e |

|

“First whip to the informer” (Доносчику первый кнут.)

Any teacher who has taught in Moscow knows that if the teacher is giving an exam the teacher cannot walk out of the room for even one minute because all of the kids will cheat; whether they're elementary school students or university students. Tolerance of dishonesty is high in the University system. With few exceptions, Russian universities do not address the issues of academic cheating (plagiarism, falsification of term papers or even various forms of gratification in return for the good grade) at institutional level. As a result, cheating is blossoming both among students and faculty and reinforcing corruption practices outside academia.

1 in 25 students admits to having paid for someone else to write at least one mid-term or final-year paper. 50% of students in economics and management, state that cheaters should receive no more than a warning if caught. Possible explanations of cheating:

In the United States, in contrast to Russia, competition among students is seen as an important intrinsic value of the educational system, a value that affects interaction between students. Thus, cheating is condemned because it is considered an unfair instrument of competition. In Contrast in Russia, the attitude to the law and to officials differ between the two countries. In the former USSR, the judicial system served as an instrument of the party, and a common view was that officials are enemies. This attitude existed toward policemen, civil servants, train conductors, and also toward teachers, and may explain the strong negative attitude toward informers among Russian students. The larger the number of students in a collective that is cheating and tolerant toward cheating, the more often the students will cheat, the more tolerant they are, and the less costly it is for every student to cheat and to be tolerant toward cheating. This is the coordination effect: the more consistently a behavioral norm is observed by members of society, the greater the costs to an individual who don’t follow this behavior. Since cheating is widespread and group loyalty a deeply held value, informants and those seeking reform can be seen in a negative light. As an old Russian proverb goes, “First whip to the informer.” In addition, there remains a lot of social pressure to be a team player, even in a corrupt environment.

|

Friends - the key to getting anything done in Russia

e |

|

Better to have one hundred friends than one hundred rubles (Не имей сто рублей, а имей сто друзей).

The value of the Russian ruble may increase or decrease but not the value of Russian friends. Friends and familiar faces are the key to getting things done in Russia, and foreigners who cultivate close relationships will have a big advantage in doing business there. Sol Hurok, the legendary American impresario who pioneered North American tours by Soviet dance and music groups, would visit the Soviet Union periodically to audition performing artists and to select those he would sign for performances abroad. Traveling alone, Hurok would negotiate and sign contracts for extensive U.S. coast-to-coast tours by such large ensembles as the Bolshoi Ballet and the Moscow Philharmonic. In Moscow in 1969 author Yale Richmond asked Hurok how he could sign contracts for such large and costly undertakings without lawyers and others to advise him. “I have been coming here for many years and doing business with the Russians. I simply write out a contract by hand on a piece of paper, and we both sign it. They know and trust me.”[74] William McCulloch is an American whose business activities in Russia include housing construction and telecommunications. The key to doing business in Russia, says McCulloch, is finding the right partner—one with whom a basis of trust is established over time. “You cannot bring in an army of New York lawyers and have an ironclad deal. You have to have a clear understanding with the right partner about what you are doing.” Such an understanding, he adds, makes it possible to negotiate one’s way through the Russian political, economic, and banking systems.[75] Russians rely on a close network of family, friends, and coworkers as protection against the risks and unpredictability of daily life. In the village commune, Russians felt safe and secure in the company of family and neighbors. Today, in the city, they continue to value familiar faces and mistrust those they do not know. Visitors who know a Russian from a previous encounter will have a big advantage. First-time travelers to Russia are advised to ask friends who already know the people they will be meeting to put in a good word for them in advance of their visits. And ideally the same traveler should return for subsequent visits and not be replaced by someone else from the firm or organization whose turn has come for a trip to Russia. Despite its vast size, or perhaps because of it, Russia is run on the basis of personal connections. In both the workplace and in private life, Russians depend on those they know—friends who owe them favors, former classmates, fellow military veterans, and others whom they trust. The bureaucracy is not expected to respond equitably to a citizen’s request. Instead, Russians will call friends and ask for their help. The friendship network also extends to the business world. Business managers, short of essential parts or materials, will use their personal contacts to obtain the necessary items. Provide a spare part or commodity for someone, and receive something in return. Without such contacts, production would grind to a halt. Westerners who want something from their government will approach the responsible official, state their case, and assume that law and logic will prevail. Russians in the same situation, mistrustful of the state and its laws, will approach friends and acquaintances and ask them to put in a good word with the official who will decide. The process is reciprocal: those who do favors for Russians can expect favors in return.

The word friend, however, must be used carefully in Russia. An American can become acquainted with a complete stranger and in the next breath will describe that person as a friend. American friendships, however, are compartmentalized, often centering around colleagues in an office, neighbors in a residential community, or participants in recreational activities. This reflects the American reluctance to get too deeply involved with the personal problems of others. An American is more likely to refer a needy friend to a professional for help rather than become involved in the friend’s personal troubles. Not so with Russians, for whom friendship is all encompassing and connotes a special relationship. Dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov, when asked about the difference between Russian and American friendships, replied:

The Russian language has different words for friend (drug, pronounced “droog”) and acquaintance (znakomy), and these words should not be misused. A drug is more like a “bosom buddy,” someone to trust, confide in, and treat like a member of the family. Such friendships are not made easily or quickly. They take time to develop, but when they are made and nurtured, a Russian friendship will embrace the entire person. Russians will ask friends for time and favors that most Americans would regard as impositions. Friendship with a Russian is not to be treated lightly. One American describes it as smothering, and some will find that it is more than they can handle. As one Russian explained, “Between Russian friends, what’s theirs is yours and what’s yours is theirs, especially if it’s in the refrigerator.” Americans tend to be informal in their speech—candid, direct, and without the rituals, polite forms, and indirect language common to many other cultures. Russians welcome and appreciate such informal talk, but usually only after a certain stage in the relationship has been reached. The preferred form of address among Russians and the one most likely to be used in the initial stage of a relationship, is the first name and patronymic (father’s name plus an affix). For example:

With the friendship stage comes the use of the first name by itself, or a nickname. But first-name usage with a foreigner does not necessarily indicate that the friendship stage has been reached, as it would with another Russian. It does signify, however, the next stage in a developing relationship. Like most European languages, Russian has two forms of you. The more formal vi is used between strangers, acquaintances, and in addressing people of higher position. The informal ti, akin to the old English thou and the French tu or German du, is reserved for friends, family members, and children; it is also used in talking down to someone and addressing animals. Readers will surely appreciate the need for care in using the familiar form.[77]

|

The Importance of Equality

e |

|

The interests of distribution and egalitarianism always predominated over those of production and creativity in the minds and emotions of the Russian intelligentsia.

Americans are raised on the success ethic: work hard, get ahead, be successful in whatever you do. The success ethic, however, is alien to many Russians, who believe that it may be morally wrong to get ahead, particularly at the expense of others. Russians will not mind if their American acquaintances are successful, but they are likely to resent fellow Russians who “succeed.” Belief in communism has eroded, but the egalitarian ethic still survives. Nina Khrushcheva wrote: "In Russia equality of outcomes,” a belief that material conditions in society should not vary too greatly among individual and classes, wins out over Western "equality of opportunities," which tends to tolerate and even encourage the open flourishing of class distinctions. Therefore, working for money, for example, a virtue so respected in the West, was not a “good way” in Russia. Russians can be great workers, as long as labor is done not for profit but for some spiritual or personal reason or is done as a heroic deed, performing wonders, knowing no limits.[78] Equality is a social philosophy that advocates the removal of inequities among persons and a more equal distribution of benefits. In its Russian form egalitarianism is not an invention of communists but has its roots in the culture of the mir which, as we have seen, represented village democracy, Russian-style. The mir’s governing body was an assembly composed of heads of households, including widowed women, and presided over by a starosta (elder). Before the introduction of currency, mir members were economically equal, and equality for members was considered more important than personal freedom. Those agricultural communes, with their egalitarian lifestyle and distribution of material benefits, were seen by Russian intellectuals as necessary to protect the peasants from the harsh competition of Western individualism. Individual rights, it was feared, would enable the strong to prosper but cause the weak to suffer. Others saw the mir as a form of agrarian socialism, the answer to Russia’s striving for egalitarianism. For much of Russian history, peasants numbered close to 90 percent of the population. By 1990, however, due to industrialization, the figure had dropped to about 30 percent. But while the other 70 percent of the population live in urban areas, most of today’s city dwellers are only one, two, or three generations removed from their ancestral villages. Despite their urbanization and education, the peasant past is still very much with them, and many of them still think in the egalitarian terms of the mir. The Soviet Union also thought in egalitarian terms. Communism aimed to make a complete break with the past and create a new society, but its leaders could not escape the heritage of the past, and their leveling of society revived the communal ethic of the mir on a national scale. As British scholar Geoffrey Hosking observed:

Many aspects of Russian communism may indeed be traced to the mir. The meetings of the village assembly were lively, but decisions were usually unanimous and binding on all members. This provided a precedent for the communism’s “democratic centralism,” under which issues were debated, decisions were made that all Party members were obliged to support, and opposition was prohibited. Peasants could not leave the mir without an internal passport issued only with permission of their household head. This requirement was a precursor not only of Soviet (and tsarist) regulations denying citizens freedom of movement and resettlement within the country, but also of the practice of denying emigration to those who did not have parental permission. Under communism, the tapping of telephones and the perusal of private mail by the KGB must have seemed natural to leaders whose ancestors lived in a mir where the community was privy to the personal affairs of its members. And in a society where the bulk of the population was tied to the land and restricted in movement, defections by Soviet citizens abroad were seen as treasonous. Despite its egalitarian ethic, old Russia also had an entrepreneurial tradition based in a small merchant class called kupyechestvo. Russian merchants established medieval trading centers, such as the city-state of Novgorod, which were independent and self-governing until absorbed by Muscovy in the late fifteenth century. Merchants explored and developed Siberia and played a key role in Russia’s industrialization of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Merchants were also Westernizers in the years between the revolutions of 1905 and 1917, endorsing social and legal reform, the rule of law, civil liberties, and broader educational opportunities. However, they rejected economic liberalism, with its emphasis on free trade in international exchange and free competition in the domestic economy, and advocated instead state planning. And as an additional link in the chain of continuity between the old and new Russia, as Ruth Roosa has pointed out, merchants in the years prior to 1917 called for state plans of 5, 10, and even 15 years’ duration that would embrace all aspects of economic life.[80] Agriculture in old Russia also had its entrepreneurs. Most of the land was held in large estates by the crown, aristocracy, and landed gentry, but after the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, a small class of independent farmers emerged. By 1917, on the eve of the Revolution, some 10 percent of the peasants were independent farmers. The more enterprising and prosperous among them were called kulaks (fists) by their less successful and envious brethren who had remained in the mir. But the kulaks were ruthlessly exterminated and their land forcibly collectivized by the communists in the early 1930s. Millions of peasants left the land they had farmed, production was disrupted, and more than five million died in the resulting famine. The forced collectivization contributed to the eventual failure of Soviet agriculture. Private farming returned to Russia in the late 1980s and grew steadily over the following years, encouraged by Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika, legislation passed by the Russian parliament, and decrees issued by Boris Yeltsin. The legal underpinning for agricultural reform was provided by Article 36 of the new Russian constitution, approved by the electorate in December 1993, which affirmed that “Citizens and their associations shall be entitled to have land in private ownership.” Parliament, however, reflecting historic attitudes on communal ownership of land, balked at passing legislation that would have put that article into effect. The opposition in parliament was led by the Communist and Agrarian Parties, and most land remained government property, as it was during Soviet times when Communist ideology required that the state own the means of production.[81] That changed on October 26, 2001, when Vladimir Putin, drawing to close a decade of efforts by Russia’s leadership to ease Soviet-era land sale restrictions, put his pen to legislation giving Russians the right to purchase land. However, the new land code affected only some 2 percent of Russian land, and it covered purchases only for industrial, urban housing, and recreational purposes, but not for farmland. Another law, passed in 2003, finally granted rights to private ownership of land and the possibility for sale and purchase of agricultural land. However, opposition to private land ownership is still strong. Opponents of farmland sales, in addition to their ideological misgivings, believe that such sales will open the way for wealthy Russians and foreign investors to buy up large tracts of land. Foreigners have the right to buy commercial and residential land but not farmland, although long-term leases by foreigners are permitted. Supporters of farmland sales believe this will further Russia’s transition to a market economy, encourage foreign investment, improve agricultural productivity, promote growth of a property-owning class, provide revenue by taxing privately owned land, and curb the corruption that has facilitated illegal land transactions. Despite all the supportive legislation and decrees, private agriculture is still not widely accepted by Russian peasants, most of whom oppose reform and are reluctant to leave the security of the former collective and state farms for the risks of the free market. Impediments to private farming include difficulties in acquiring enough land and equipment to start a farm, a general lack of credit, the reluctance of peasants to give up the broad range of social services provided by the collective and state farms, and a fear that if land reform is reversed they will once more be branded as kulaks and will lose their land.[82] Despite its large size, Russia has relatively little area suited for agriculture because of its arid climate and inconsistent rainfall. Northern areas concentrate mainly on livestock, and southern parts and western Siberia produce grain. Restructuring of former state farms has been a slow process. Nevertheless, private farms and individual garden plots account for over one-half of all agricultural production.[83] Economic reforms have also been slow to gain support among the general public, particularly with the older generation. While there is a streak of individualism in many Russians, the entrepreneurial spirit of the businessperson and independent farmer runs counter to Russian egalitarianism. For many Russians, selling goods for profit is regarded as dishonest and is called spekulatsiya (speculation). Russians, it has been said, would rather bring other people down to their level than try to rise higher, a mentality known as uravnilovka (leveling). As Vladimir Shlapentokh, a professor at Michigan State University, points out:

|

Russia’s “American Dream”

e |

|

Russia has a less known "American dream" themselves, referred to as the "Russian idea". Russian government officials have made repeated appeals for a renewal of moral values and the search for a new “Russian idea” to embody them. President Vladimir Putin repeatedly stated that Russia’s renewal depends not only on economic success or correct state policies but on a revival of moral values and national spirit, and he has called for a new "Russian idea" that emphasizes patriotism, social protections, a strong state, and great-power status. As Georgy Poltavchenko, governor of Saint Petersburg from 2011-2018 explained:

That idea presumes a unique Russian way, with values superior to those of the materialist, individualistic, and decadent West, an idea that has also been embraced by various nationalist and communist political parties. Among those taking up the "Russian idea" are the neo-Eurasianists (неоевразийство), who trace their roots to a movement that originated among Russian exiles in Western Europe in the early 1920s. Economic geographer Pyotr Savitsky, wrote in 1925:

Today’s Eurasianists also reject the West and see Russia’s future in the East. They advocate a union of the three Slavic peoples—Russians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians—and a federation of the Slavic peoples with their Turkic neighbors to the south and east in a political union that looks strikingly similar to the former Soviet Union—and with the Russians in charge. Among the more prominent Eurasianists are Gennadi Zyuganov, leader of the Russian Communist Party, and Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the ultranationalist leader of the Liberal Democratic Party. The main components of the Russian idea are:

The “American Dream” roots are:

The “Russian idea” roots are:

|

Russians are cautious and deeply conservative

e |

|

The slower you go, the further you’ll get.

Caution and conservatism are also legacies of the peasant past. Barely eking out a living in small isolated villages, peasants had to contend not only with the vagaries of nature but also with the strictures of communal life, authoritarian fathers, all-powerful officials, and reproachful religious leaders. In a traditional agricultural society, stability was valued and change came slowly. As Marshall Shulman of Columbia University once put it, "Russians feel obliged to defend their traditional values against the onslaught of the modern world."[88] The experience of the twentieth century has given Russians no cause to discard their caution: The entire Soviet historical experience with its particular combination of majestic achievements and mountainous misfortunes. Man-made catastrophes have repeatedly victimized millions of ordinary citizens and officials alike—the first European war, revolution, civil war, two great famines, forcible collectivization, Stalin's terror, World War II, [Gorbachev failed market reforms and Yeltsin’s chaos in the 1990s]. Out of that experience, which for many people is still...deeply felt, have come the joint pillars of today's Soviet conservatism: a towering pride in the nation's modernizing, war-time, and great-power achievements, together with an abiding anxiety that another disaster forever looms and that any significant change is therefore "some sinister Beethoven knock of fate at the door."' Such a conservatism is at once prideful and fearful and thus doubly powerful. It influences most segments of the Soviet populace, even many dissidents. It is a real bond between state and society—and thus the main obstacle to change. Caution and conservatism can also be seen at the highest levels of government, where most of the leadership has been of peasant origin. Reflecting their peasant past, Russia’s leaders will take advantage of every opportunity to advance their cause but will be careful to avoid undue risk. The cautious approach was recommended by Mikhail Gorbachev in a talk in Washington during his June 1990 summit meeting with President George H.W. Bush. Noting that he preferred not to act precipitously in resolving international differences, Gorbachev advocated an approach that "is more humane. That is, to be very cautious, to consider a matter seven times, or even 100 times before one makes a decision."[89] Boris Yeltsin was also overly cautious when it was in his interest and Russia’s to be bold and daring. In June 1991, when he enjoyed high prestige and popularity after his election as president, and in August of that year after he foiled an attempted coup, Yeltsin’s caution prevented him from instituting the broad reforms that Russia required. As for Putin, if there is one word to describe him it is cautious. Andrew Jack, former Moscow bureau chief of London’s Financial Times, describes Putin as a cautious president who is very hard to categorize:

Some speak of a hereditary Russian inertia. As an old Russian proverb puts it, “The Russian won’t budge until the roasted rooster pecks him in the rear.” Americans will have their patience tested by Russian caution. A nation of risk takers, most Americans are descendants of immigrants who dared to leave the known of the Old World for the unknown of the New. In the United States, risk takers have had the opportunity to succeed or to fail in the attempt. Indeed, risk is the quintessence of a market economy. The opportunities of the New World, with its social mobility and stability, have helped Americans to accentuate the positive. For Russians, geography and history have caused them to anticipate the negative.[91] |

Russians Extremes and Contradictions

e |

|

The American mind will not apprehend Russia until it is prepared philosophically to accept the validity of contradiction. Soberly viewed, there is little possibility that enough Americans will ever accomplish...philosophical evolutions to permit...any general understanding of Russia on the part of our Government or our people. It would imply a measure of intellectual humility and a readiness to reserve judgment about ourselves and our institutions, of which few of us would be capable. For the foreseeable future the American, individually and collectively, will continue to wander about in the maze of contradiction and the confusion which is Russia, with feelings not dissimilar to those of Alice in Wonderland, and with scarcely greater effectiveness. He will be alternately repelled or attracted by one astonishing phenomenon after another, until he finally succumbs to one or the other of the forces involved or until, dimly apprehending the depth of his confusion, he flees the field in horror. Distance, necessity, self-interest, and common-sense may enable us, thank God, to continue that precarious and troubled but peaceful co-existence which we have managed to lead with the Russians up to this time. But if so, it will not be due to any understanding on our part. "West and East, Pacific and Atlantic, Arctic and tropics, extreme cold and extreme heat, prolonged sloth and sudden feats of energy, exaggerated cruelty and exaggerated kindness, ostentatious wealth and dismal squalor, violent xenophobia and uncontrollable yearning for contact with the foreign world, vast power and the most abject slavery, simultaneous love and hate for the same objects...the Russian does not reject these contradictions. He has learned to live with them, and in them. To him, they are the spice of life."

President Harry Truman once quipped that he was looking for a one-armed economist because all his economic advisers concluded their advice by saying, “But, on the other hand...” Americans, with their proclivity for rational consistency seek clear and precise responses, but they usually end up by falling back to a middle position that avoids contradictions and extremes. Russians, by contrast, have a well-deserved reputation for extremes. When emotions are displayed, they are spontaneous and strong. Russian hospitality can be overwhelming, friendship all encompassing, compassion deep, loyalty long lasting, drinking heavy, celebrations boisterous, obsession with security paranoid, and violence vicious. With Russians, it is often all or nothing. Halfway measures simply do not suffice. George F. Kennan, the U.S. diplomat and the "Father of Russian Containment" wrote:

1. west and east, 2. Pacific and Atlantic, 3. arctic and tropics, 4. extreme cold and extreme heat, 5. pro-longed sloth and sudden feats of energy, 6. exaggerated cruelty and exaggerated kindness, 7. ostentatious wealth and dismal squalor, 8. violent xenophobia and uncontrollable yearning for contact with the foreign world, 9. vast power and the most abject slavery, 10: simultaneous love and hate for the same objects: ...these are only some of the contradictions which dominate the life of the Russian people. The Russian does not reject these contradictions. He has learned to live with them, and in them. To him, they are the spice of life. He likes to dangle them before him, to play with them philosophically...for the moment, he is content to move in them with that same sense of adventure and experience which supports a young person in the first contradictions of love. The American mind will not apprehend Russia until it is prepared philosophically to accept the validity of contradiction. It must accept the possibility that just because a proposition is true, the opposite of that proposition is not false....It must learn to understand that Russian life at any given moment is not the common expression of harmonious, integrated elements, but a, precarious and ever shifting equilibrium between numbers of conflicting forces. Russian extremes and contradictions have also been described by poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko:

Human feelings count for much in Russia, and those who do not share the depth of those feelings will be considered cold and distant. When Russians open their souls to someone, it is a sign of acceptance and sharing. Westerners will have to learn to drop their stiff upper lips and also open their souls.[93] |

Big is Beautiful

e |

|

In its grandiose schemes, which were always on a worldwide scale, communism makes use of the Russian disposition for making plans and castle-building, which had hitherto no scope for practical application.

"Sire, everything is done on a large scale in this country — everything is colossal."[94] Said the Marquis de Custine, addressing Tsar Nicholas in St. Petersburg in 1839 at the start of his travels through Russia. The French aristocrat was moved by the grand scale of “this colossal empire,” as he described it in his four-volume Russia in 1839.

Soviet leaders continued that “colossalism.” When they industrialized, centralizing production to achieve economies of scale, they built gigantic industrial complexes employing up to 100,000 workers. Gigantomania is the term used by Western economists to describe that phenomenon. The Palace of Soviets, a Stalin project of the 1930s, was to have been the tallest building in the world, dwarfing the Empire State Building and the Eiffel Tower, and be topped by a 230-foot statue of Lenin. The Kremlin’s Palace of Congresses, the huge hall known to Western TV viewers as the site of mass meetings, seats 6,000 and is one of the world’s largest conference halls. Its snack bar can feed 3,000 people in 10 minutes. In Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad), the site of a decisive battle with Germany in World War II, a victorious Mother Russia, the largest full-figure statue in the world, towers 282 feet over the battlefield. And Russia’s victory monument to World War II, completed in 1995, is 465 feet high and topped by a 27-ton Nike, the goddess of victory. Aeroflot was by far the world’s largest airlines, flying abroad as well as to the far corners of the Soviet Union. Its supersonic transport (SST), the world’s first, was considerably larger than the Anglo-French Concorde. Russians are impressed with size and numbers, and much that they do is on a grandiose scale. That is not unusual for a vast country. Russians think and act big, and they do not do things in a half-hearted way. Nor are these traits uniquely Russian. Americans, accustomed to wide open spaces and with an expansive outlook on life, also are known to think big. Big also describes the Russian military. Even after large reductions, the Russian military in 2008 had more than one million personnel under arms. It also had the biggest missiles, submarines, and aircraft. Russia’s grandiose plans have at times been realized but at other times not. The Tsar Bell was too heavy and was neither hung nor rung. The Tsar Cannon was too big to fire. The Palace of Soviets was abandoned after the foundation proved incapable of supporting the huge structure, and the site was used for an outdoor swimming pool—one of the largest in Europe, of course. The Soviet SST had major design problems and was shelved after several crashes, including one at the prestigious Paris Air Show. Aeroflot’s extensive domestic network was broken up into nearly 400 separate companies, with a drastic decline in safety standards. Russia’s huge industrial plants have proven to be highly inefficient and noncompetitive, and the large state subsidies they require to avoid bankruptcy are an obstacle to their privatization. The Russian army’s combat capabilities, as confirmed in the Chechnya war, have dramatically declined. And the Kursk, pride of the Russian navy and one of the largest submarines ever built, suffered an unexplained explosion in August 2000, and sank to the bottom of the Barents Sea with the loss of its entire crew of 118. Russians still have grand designs. In April 2007, Russia announced the revival of an old plan from its tsarist years to build a tunnel under the Bering Sea that would link Siberia with Alaska. And what should be said of Moscow’s current politics, the most recent of many attempts to reform Russia? The objective this time is to modernize Russia, to make it more competitive with the West, and to regain its superpower status. Will the sweeping reforms succeed or are they merely the latest example of Russians thinking too big? History tells us to believe the latter. As Anton Chekhov put it over 100 years ago, “A Russian is particularly given to exalted ideas, but why is it he always falls so short in life? Why?”[95] |

Russians superiority complex (Messianism)

e |

|

All Russians have a superiority complex, that we're still equal to the United States.

The [Westerners] disappear, everything collapses….the papacy of Rome and all the kingdoms of the West, Catholicism and Protestantism, faith long lost and reason reduced to absurdity. Order becomes henceforth impossible, freedom becomes henceforth impossible, and [Westernern] civilization commits suicide on top of all the ruins accumulated by it. … And when we see rise above this immense wreck this even more immense Eastern Empire like the Ark of the Covenant, who could doubt its mission...

Fyodor Tyutchev, a Russian diplomat and poet, wrote those words in 1848 in response to the liberal revolutions sweeping Western Europe in that year. He saw Western civilization as disintegrating while Russian civilization, morally and spiritually superior, was rising. Russian Orthodox Christianity with its mystical and otherworldly perspective is believed to have imparted on Russian politics a grand image of Russia's spiritual destiny to guide mankind.[97] Messianism is still alive in Russia today particularly among intellectuals on the left as well as the right, who share a belief and pride in Russia as a great power with a special mission in the world. Economist Mikhail F. Antonov, for example, in an interview with The New York Times Magazine, stated:

Russian thinkers past and present seek to excuse Russia's material backwardness by acclaiming her correctness of cause, spiritual superiority, and messianic mission. Serge Schmemann of The New York Times writes:

A similar view was espoused by a contemporary Russian philosopher when author Yale Richardson asked him about Russia’s role in the world. “Russia is European on the surface, but deep inside it is Asian, and our link between Europe and Asia is the Russian soul. Russia’s mission is to unite Europe and Asia.”[100] Such messianic missions are common throughout the history of America, who have always believed that they have something special to bring to the less fortunate — Christianity to heathens, democracy to dictatorships, and the free market to state-run economies. Americans who believe in their own mission should be sensitive to Russian messianism and fears for the future. Without great-power status, Russians fear that other countries will no longer give them the respect they are due and Russia will lose its influence in the world. Along with messianism, there is also a Russian tendency to blame others for their misfortunes, which has a certain logic. If Russians are indeed the chosen people and have a monopoly on truth, then others must be the cause of their misfortunes. Freemasons and Jews, among others, have often been blamed in the past for Russia’s troubles.

|

Russians’ rebellious spirit

e |

|

Не приведи Бог видеть русский бунт, бессмысленный и беспощадный!

The Russians’ patience sometimes wears thin and they rebel. History is replete with rebellions of serfs against masters, peasants against gentry, Cossacks against lords, nobles against princes, and communists against commissars — usually with mindless destruction and wanton cruelty. There is also a record of revolt from within — palace revolutions — in the time of general secretaries and presidents as well as tsars, as Mikhail Gorbachev learned in August 1991 when a junta attempted to seize power in Moscow, and as Boris Yeltsin learned in 1993 when a similar attempt was made by hard-liners in the Russian parliament. Conspiracies, coups, insurrections, ethnic warfare, and national independence movements all reflect the instabilities and inequities of Russian society and its resistance to change. When peaceful evolution is not viable, revolution becomes inevitable. Russians have long been seen as submissive to authority, politically passive, and unswerving in policy. But when the breaking point is reached, the submissive citizen spurns authority, the docile worker strikes, the passive person becomes politically active, and rigid policies are reversed almost overnight. Such a point was reached in the late 1980s when the Soviet Union experienced food shortages, crippling strikes, a deteriorating economy, nationality unrest, ethnic warfare, movements for sovereignty or independence by the republics, inept government responses to the Chernobyl nuclear disaster and Armenian earthquake, and revelations of widespread environmental devastation. In reaction to these events, voters of the Russian Federation rebelled in June 1991. Given a choice, they rejected the candidates of communism and chose as their president Boris Yeltsin and his program of decentralization, democracy, and economic reform. Yeltsin thus became the first freely elected leader in Russian history. In August 1991, Russians rebelled again, taking to the streets of Moscow in a massive protest that helped bring down the old guard junta that had attempted to seize power. And in December 1995, disillusioned with reform, corruption, and a deep decline in their standard of living, Russians repudiated the Yeltsin administration by electing a parliament that was deeply divided between opponents and supporters of democratic and economic reforms, and between Westernizers and Slavophiles (Russians determined to protect and preserve Russia’s unique cultural values and traditions).[101]

|

Alcoholism - Russia’s Scourge

e |

|

More people are drowned in a glass than in the ocean. (В стакане тонет больше людей, чем в море.)

To all the other “-isms” that help one to understand Russians, alcoholism must unfortunately be added. For Karl Marx, religion was the opiate of the people. For Russians, the opiate has been alcohol. The Russian affinity for alcohol was described by the French aristocrat Marquis de Custine in 1839:

In 1965, the distinguished Russian novelist Andrei Sinyavsky has described drunkenness as:

Per capita consumption of alcohol in Russia and the United States is not very different. Americans, however, drink more wine and beer, Russians more hard liquor, mainly vodka. And like their North European neighbors from Ireland to Finland, Russians drink their distilled spirits “neat,” without a mixer, and in one gulp. Vodka is described by Hedrick Smith as "one of the indispensable lubricants and escape mechanisms of Russian life. … Russians drink to blot out the tedium of life, to warm themselves from the chilling winters, and they eagerly embrace the escapism it offers."[104] To take the measure of a man, Russians will want to drink with him, and the drinking will be serious. Americans should not attempt to match their hosts in drinking. This is one competition Russians should be allowed to win, as they surely will. Vodka is also a prelude to business transactions. As one Western financier explains: